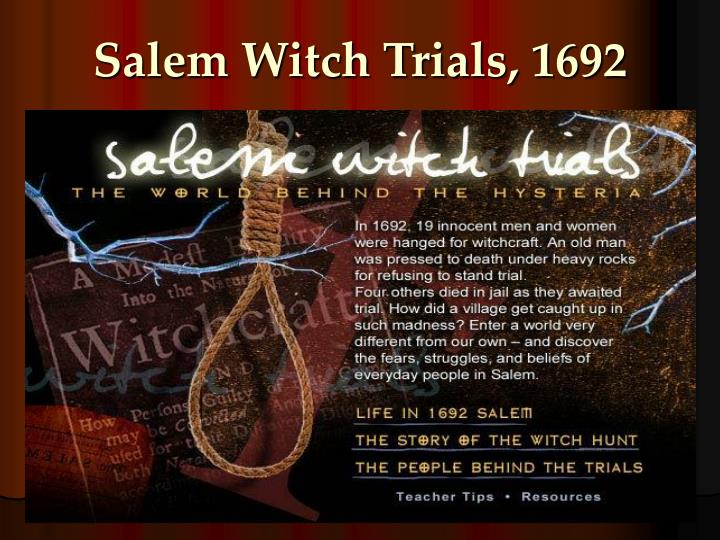

The Salem witch trials death took place in the Province of Massachusetts Bay between 1692 and 1693 in Salem. This trial began in January of 1692. A few girls were behaving strangely and a local doctor confirmed that they were bewitched. People believe that the accused witches were victims of mass hysteria.

Salem Witch Trials Victims

The Salem Witch Trials took place in Salem in the Province of Massachusetts Bay between 1692-1693. Historians believe the accused witches were victims of mob mentality, mass hysteria and scapegoating. The Salem Witch Trials began in January of 1692, after a group of girls began behaving strangely and a local doctor ruled that they were. Over 200 innocents stood accused & jailed, all paid a high price, 25 with their life. The Salem Witch Trial victims included small children, as young as 4 were accused. No one was off limits, no one was safe. A short bio on each, 25 long, such is the body count of the Salem executions.

The bewitched girls soon accused three women- Parris Indian slave, Tituba, a local beggar woman, Sarah Good, and an invalid widow Sarah Osbourne. The locals started to question the accused and they all gathered to witness the victims of the Salem witch trials come face to face with the women the girls accused of witchcraft.

- The Salem witch trials, which resulted in the executions of 19 innocent women and men, had a profound impact on the citizens of Massachusetts. To this day, the term “Witch Hunt” refers to someone being charged and often convicted in the court of public opinion with little or no evidence other than the words of someone else.

- The Salem Witch Trials Salem, Massachusetts 1692 1693 The Puritans considered Indians to be devilish and barbaric. They lived in constant fear of attack. – A free PowerPoint PPT presentation (displayed as a Flash slide show) on PowerShow.com - id: 80e08b-M2JjY.

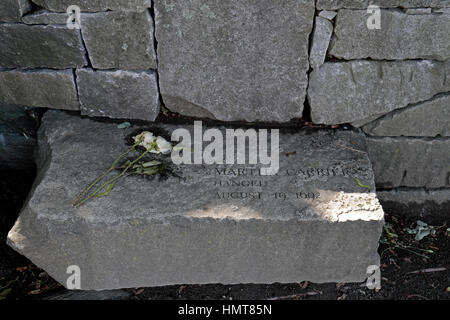

- Martha Ingalls Allen Carrier BIRTH 19 Aug 1650 Andover, Essex County, Massachusetts, USA DEATH 19 Aug 1692 (aged 42) Salem, Essex County, Massachusetts, USA BURIAL Salem Witch Trials Memorial Salem, Essex County, Massachusetts, USA Add to Map MEMORIAL ID 8298 View Source. Pictures added by S.K. Salem Witch Trial Victim.

Download Salem Witch Trials Victims Martha Carrier Freezing

Salem Witch Trials Executions

After Tituba got arrested, she spoke out saying that, she saw Satan and that she signed the devil’s book with her own blood. She also said that Osbourne and Good have also signed the book with her. Because of Tituba’s testimony, people got panicked and then a witch hunt began which swept areas beyond Salem throughout New England. More than 200 Salem witch trials people were accused of being involved in witchcraft and about 20 were executed by hanging in 1692.

1. How Many People Died in the Salem Witch Trials?

Many of the accused women were slaves, criminals, outspoken and according to the book ‘The Societal History of Crime and Punishment in America:

“A number of historians have speculated as to why the witch hunts occurred and why certain people were singled out. These proposed reasons have included personal vendettas, fear of strong women, and economic competition. Regardless, the Salem Witch Trials are a memorial and a warning to what hysteria, religious intolerance, and ignorance can cause in the criminal justice system.”

This situation resulted in imprisonment and death of many innocent people. And many accused were arrested or escaped from jail.

Few of the Salem Witches Names:

Tituba

Sarah Good

Sarah Osbourne

Arthur Abbott

Nehemiah Abbott Jr

John Alden Jr

Abigail Barker

Mary Barker

William Barker, Sr

William Barker, Jr

Sarah Bassett

Sarah Bibber

Bridget Bishop

Sarah Bishop

Mary Black

Mary Bradbury

Mary Bridges, Sr

Mary Bridges, Jr

Sarah Bridges

Hannah Bromage

Sarah Buckley

George Burroughs

Candy

Martha Carrier

Richard Carrier

Download Salem Witch Trials Victims Martha Carrier Free Download

Sarah Carrier

(redirected from Martha Carrier)Also found in: Legal.

Salem Witch Trials

(religion, spiritualism, and occult)On the afternoon of January 20, 1692, Elizabeth Parris, age nine, and Abigail Williams, age eleven, began to scream obscenities, alternate between convulsive seizures and trancelike states, and exhibit other odd behaviors that quickly grabbed the attention of their neighbors in the town of Salem, Massachusetts. Over the next few days, other girls of about the same age began to act out in similar fashion. Within a month, when no other cause could be found to explain these actions, the townspeople decided the girls must have been bewitched by Satan.

The Reverend Samuel Parris, Elizabeth's father, led prayer services with the hope of exorcising the demons. Just to make sure all the religious bases were covered, a man named John Indian—probably not his real name—baked a cake featuring ingredients of rye meal and the girls' urine. This was 'reverse magic' that was supposed to reveal the identities of the witches who had afflicted the girls.

Under such ecumenical influence, the girls confessed that a woman named Tituba, a Carib Indian slave 'owned' by the Reverend Parris, was the witch. Later confessions disclosed that Tituba was a member of a coven, along with Sarah Good and Susan Osborne.

On February 29th, warrants were issued for their arrest. Good and Osborne professed their innocence:

Judges Hathorne and Corwin: What evil spirit have you familiarity with?

Sarah Good: None.

Judges: Have you made no contract with the devil?

Good: No.

Judges: Why do you hurt these children?

Good: I do not hurt them. I scorn it.

Judges: Who do you employ then to do it?

Good: I employ no body.

Judges: What creature do you employ then?

Good: No creature. I am falsely accused.

But Tituba confessed that she often saw the devil, who looked 'sometimes like a hog and sometimes like a great dog.'

The trials continued throughout the spring and summer. By October 8th, more than twenty people, mostly women, had been found guilty and executed. Some were burned, others were hanged, and a few were squashed to death according to a quirky New England custom of building a sort of dance floor over the victim, and then holding a community party on it, involving people, horses, wagons, and anything else heavy. Many more faced the torture of being locked up in a jail cell and left to wonder what was going to happen to them.

Puritans of no less stature than the great Cotton Mather traveled from all over the area to witness the trials, taking back reports to their home churches. It was the talk of New England. Some people were probably just titillated. New England in 1692 could, after all, be a pretty dull place. And when women were publicly stripped to the waist and whipped to get them to confess, there must have been those who decided they would rather attend the public spectacle than hoe a long row of corn on a hot August afternoon. Even the courtroom debates were interesting.

But others, such as Thomas Brattle, were simply appalled. He wrote a highly articulate letter to the governor of the commonwealth, convincing him to make a declaration that no evidence of a supernatural nature could be allowed in a court of law.

That took the wind out of the sails of the prosecution, because all they had was supernatural evidence.

Then, on October 29th, Governor Phips dissolved the local court and ordered all further trials to be held before the State Superior Court. These took place in May of 1693. No one was convicted. The trials were over.

But the legend lingers on. Even today people flock to Salem to relive those scandalous ten months. Laurie Cabot (see Cabot, Laurie) has even made it her headquarters, the better to draw attention to the modern religion of Wicca (see Wicca).

Why did they do it? How could people have become so involved with supposed 'witchcraft' and 'devil worship' that they went so completely off the deep end of their religion? What happened to the words of Jesus about love and compassion?

Well, we might ask the same thing about the McCarthyism that swept the United States half a century ago. Mass hysteria is a terrible thing. But there were probably other reasons. Francis Hill, in her book A Delusion of Satan, suggests the witch trials my have been fueled by motives ranging from personal jealousy to post-traumatic stress syndrome experienced by those who fought in the American Indian wars. Fueled by sermons that questioned whether or not Indians had souls, ex-soldiers may have come to believe that the only reason the colonists suffered such bloody losses to 'ignorant savages' was that Indians were in league with the devil. Now the devil was close at hand. In a classic case of misplaced aggression, they persecuted the innocent and helpless.

We'll probably never know. But of all the dark chapters in Christian history, the time of the Salem witch trials is undoubtedly one of the worst.

Salem Witch Trials

(religion, spiritualism, and occult)The village of Salem, Massachusetts, later known as Salem Farms and today as Danvers, was the scene of the best known of American witch trials, in 1692. The village's name was taken from 'Jerusalem.' As a community of Puritans, it was extremely troubled long before the so-called 'witchcraft' manifested itself. It had had a succession of ministers, none of whom had stayed for any length of time because of disputes with the village administrators.

Before 1692 there had been a dozen or so cases of witchcraft in Massachusetts. This relatively small number was, perhaps, unusual when it is considered that the main exodus of Puritans from England to the colonies occurred during the reign of Charles I, when the persecution of witches was on the increase in England. In New England, the first victim of the persecutions that were to follow was Margaret Jones of Charlestown, who was hanged in 1648 for dispensing herbal cures. Another early victim was Ann Hibbins, who was sister to the deputy-governor of Massachusetts. The Colonial Records do not show exactly what Ann Hibbins was charged with; they merely contain the verdict and death-warrant. The Rev. John Norton, the persecutor of the Quakers, is on record as saying that Ann Hibbins was hanged 'only for having more wit than her neighbors.'

In 1688, the case of the Goodwin children involved a Catholic Irishwoman named Glover, laundress to the Goodwin household. The case was similar in many ways to the later Salem case, with four children accusing the old woman of bewitching them. The Rev. Cotton Mather took a special interest in this case, as he did with the case in Salem.

Both the Goodwin children and the children of Salem knew exactly how a witch was supposed to behave. Tracts and chapbooks on the subject were plentiful. Details of the latest trials in England were published and soon found their way to the New World. In New France and New England (1902), John Fiske wrote, 'In 1692, quite apart from any personal influence, there were circumstances which favored the outbreak of an epidemic of witchcraft. In this ancient domain of Satan there were indications that Satan was beginning again to claim his own. War had broken out with that Papist champion, Louis XIV, and it had so far been going badly with God's people in America. . . . Evidently the Devil was bestirring himself; it was a witching time; the fuel for an explosion was laid, and it needed but a spark to fire it. That spark was provided by servants and children in the household of Samuel Parris, minister of the church of Salem.'

Samuel Parris had lived for some years in Barbados, in the Caribbean, where, before turning his attention to theology, he had acquired two servants named Tituba and John Indian. When he was offered the position of minister to Salem Village, a lengthy correspondence took place before an agreement was reached. This was due to the village's reputation for miserliness when it came to supporting its pastor. It was finally agreed that Parris would be paid sixty-six pounds a year, with only one-third paid in cash and the balance in goods. He would have to chop his own firewood and keep the fence around his property in good repair. There was also provision that 'if God shall diminish the estates of the people, that then Mr. Parris do abate of his salary according to proportion.'

Parris's family consisted of his wife, their daughter Betty, aged seven, and Betty's cousin Abigail Williams, aged nine. The two children were generally in the care of Tituba, who would give them small chores in the kitchen and around the house. In a Puritan community, boys would work in the fields with the men while girls worked in the house. The two girls in the Parris home were smart enough to know that Tituba would rather sit and tell them stories of life in the West Indies than do a lot of hard work. It wasn't long before a number of their friends joined them in the parsonage kitchen, sitting and listening to these stories. The friends included Ann Putnam, aged twelve, Mary Walcott and Elizabeth Hubbard, both seventeen, Elizabeth Booth and Susannah Sheldon, both eighteen, and Mary Warren and Sarah Churchill, both twenty. They were occasionally joined by Mercy Lewis, seventeen, a servant in the Putnam household.

Exactly what Tituba told the children is not known, but it is highly probable that the stories were flavored with tales of Voodoo and magic. It is also highly probable that the children would try to reenact some of the anecdotes they heard, even to the extent of going into trances and uttering mystical words. Voodoo, as practiced in Haiti and other islands of the Caribbean, is a polytheistic religion with a priesthood and set forms of worship. One of the main reasons for a Voodoo ceremony is to commune with the gods, or loa, to the extent that those deities manifest their presence by taking possession of the worshipers. The main male deity is Damballah-Wédo, who is a serpent god. When possessed by him, the worshiper will initially writhe on the floor and hiss, like a snake. One of the early signs of 'possession' of the Salem children was that they crawled on the floor, barking like dogs. Probably being more familiar with dogs than with snakes, this would seem to be an interpretation of Tituba's stories being acted out by the children.

Early in January 1692, young Betty's parents noticed that she was having what seemed to be mild fits. She would sit and stare into space for long periods, then, when reprimanded, would cough and splutter and, according to her father, bark like a dog. Soon Abigail, her cousin, started doing the same thing, and both girls would get down on the floor and crawl around the furniture doing their barking. Parris called in the Elders of the village and they all prayed over the girls, but to no avail. Doctor Griggs was then called in to examine them. Finding nothing wrong, he commented that perhaps the girls were bewitched. This called for a renewal of the prayers said over the girls. No one seemed to notice that whenever they had their fits, the girls would merely indulge in all the playful things normally forbidden young, high-spirited children in such a community. They would shout and scream, roll on the floor and climb on the furniture, even throw things—including the Bible—about the room. It was not long before the other girls in their Tituba circle joined with them in such activity.

People remembered the case of the Goodwin children, since Mather's book on the subject had received wide circulation. There was probably a copy of it even in the Parris household. Parris himself called in neighboring clergy, who flocked to see the 'Afflicted Children.' Among them, the Rev. Nicholas Noyes came from the First Church in Salem Town and John Hale came from nearby Beverly. Hale had previously dealt with witchcraft cases in his own area, although he had been loathe to act in them. With this distinguished audience, the girls may have realized that they had gone too far, but possibly it seemed too late to back out. Soon they were being urged to name the person who had bewitched them.

Young Ann Putnam rapidly became the leader of the group of girls. She had a mother, also named Ann, who was well educated but very highly strung, having lost a number of children at birth before finally bearing Ann. Her sister had also suffered this way, finally dying in childbirth. It seemed possible that the elder Ann was using her daughter as a go-between with Tituba to try to make contact with the dead.

Abigail Williams, young Betty's cousin, would put on a tremendous show, howling louder than the rest as the clergy prayed over them. The ministers, for their part, started naming people to see if there was any reaction from the girls at hearing the names. Finally the girls realized that they would have to name someone. Betty, the youngest, mentioned Tituba's name, although it seems uncertain whether this was meant as a charge against the woman. The men leapt at the name and asked if indeed Tituba had done the bewitching. Other girls agreed that she had. They also added the names of Goody (Goodwife) Osburn and Goody Goode. Sarah Goode was a beggar woman in the village with a bad reputation. She smoked a pipe and had a quick, coarse tongue. It was believed by the villagers that she had been responsible in some way in the recent smallpox epidemic, spreading the disease through her general uncleanliness and negligence. She had a number of children and was at that time pregnant again. Sarah Osburn also had no good name in the village, although at that time she was bedridden. She was a widow but had lived with her second husband, William, for a number of years before marrying him. Tituba and the two Goodwives were arrested, and the village felt it could breathe again.

The preliminary hearing, to determine whether the case should go to trial was to have been held in Deacon Ingersoll's Ordinary in the village. However, so many people turned out for the event that it had to take place in the church. The magistrates were Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne (an ancestor of the novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne). Neither man had any legal training, since the practice of law was not permitted in the Puritan colony. Before embarking on the hearing, therefore, both men studied Cotton Mather's recent work on the Goodwin case and such books as Bernard's Guide to Jurymen and Glanville's Collection of Sundry Tryals in England. On searching through the Bible, they would have found no definition of witchcraft. In fact, the word itself was hardly used, especially in editions predating the King James version that was so heavily biased due to James's own personal fear of what he saw as witchcraft.

The accused were not legally represented in any way, and they were presumed guilty before the start. The hearing commenced on Tuesday, March 1, and the first to be interviewed was Sarah Goode. She was openly defiant, disclaiming any knowledge of the affair. However, several people testified that there had been times when Goody Goode had come begging and been turned away. On leaving she had been seen to mutter to herself and, a day or so later, a chicken would stop laying or a cow would run dry of milk. This seemed proof conclusive.

Sarah Osburn was obviously a sick woman, having been taken from her bed to the prison and then needing assistance to appear in court. Whenever she looked at the 'afflicted children,' who were present, they would start going into their fits again. Other than that there was little evidence against her. But when Tituba was brought in, she caused quite a sensation. She did not attempt to deny anything; in fact, she claimed that she was a witch. For three days she told her tales. She said that she had been approached by a 'tall man from Boston' who wanted her to sign her name in his book. She said that both Goody Goode and Goody Osburn already had their names there. In fact, she said, there were nine names in the book. This last claim caused much disquiet, since it meant that there were still more witches to be tracked down.

The three accused were moved to Boston, where, a few weeks later, both Sarah Osburn and the child she was carrying died in their cell. Young Betty Parris was sent to stay with friends in Salem Town. Separated from the other girls, her fits quickly ceased. John Proctor managed to cure his servant of her affliction, if only for a while, by promising her a beating if the fits continued. However, over his protests, Mary Warren was called back to court by the magistrates. The elders and ministers had continued to pray over the girls in an attempt to learn the identities of the other witches. Ann Putnam soon provided the name of Martha Corey, an outspoken woman who had moved to the village from Salem Town only a year previously. The main reason for suspicion, in her case, seems to have been the fact that Martha Corey had been loud in her disbelief of witchcraft.

The newly accused started out by denying all and saying that the girls should not be believed. From then on, everything that Martha Corey did, the children copied. If she bit her lip, they all bit theirs, till the blood ran, saying that she made them do it. One of the girls claimed to be able to see 'the Black Man' standing beside the woman and whispering in her ear.

The next to be 'cried out upon' by the girls, once again led by Ann Putnam, was the aged and extremely deaf Rebecca Nurse. Rebecca was in her seventies and had been confined to her bed for almost a year. For her whole life she had been regarded as a pillar of the community and a devout Christian. The main charge against her seemed to have been that while she lay seemingly immobile in her bed, her 'shape'—her etheric double—was running around the community wreaking havoc. Or so claimed the afflicted children.

At Rebecca Nurse's trial, a petition was presented to the magistrates, signed by thirty-nine people and attesting to Rebecca's good character. Yet while she was on the stand the children had their usual fits. At one point, when Magistrate Hathorne seemed affected by her straightforward answers, Ann Putnam senior cried out, 'Did you not bring the Black Man with you? Did you not bid me tempt God and die? How often have you eaten and drunk your own damnation?' Rebecca raised her hands to heaven in despair. The girls took this as a signal and went into violent fits. Hathorne decided that it was the accused's raised hands that had caused the fits, and Nurse was sent to jail to await trial.

Arrests continued from there until, by the end of spring, at least 125 people were in prison. Among them were John Proctor and George Jacobs, masters to two servant girls who were among the afflicted children. Another man, John Willard, had commented that it was the girls who were the real witches and who were deserving of the gallows. He was instantly cried out upon.

Perhaps the most amazing arrest was that of the Reverend George Burroughs. He had been minister in Salem Village from 1680 to 1682 and had left because of various feuds within its church. To his later sorrow, he had been on the opposite side of the feud from the senior Ann Putnam. He had settled in Wells, Maine. He was arrested there at the beginning of May and was taken to Salem to answer the charge of witchcraft. In a prior consultation with other ministers, it had come out that he had only had his eldest son baptized and that he could not remember when he had last served the Lord's Supper. This was damning evidence. He was stripped and searched for the Devil's Mark, but without success.

By the middle of May, the first royal governor, Sir William Phips, had arrived with a new charter replacing the provisional government of Massachusetts that had followed the overthrow of Andros. On Phips's departure again for a few months, a special court of 'Oyer and Terminer' (meaning 'to hear and determine') was appointed to try the witchcraft cases. This was presided over by William Stoughton, who, with Samuel Sewell, joined Hathorne and Corwin.

The evidence against Burroughs came mainly from Ann Putnam the elder. He was charged, among other things, with murder of a spectral nature. It was claimed that whenever a soldier from the village was killed in the Indian fighting, Burroughs was responsible. His first two wives appeared in ghostly form—visible only to the children—to testify that he had murdered them. Burroughs had always been exceptionally strong for his size, and this was now held against him. Where he had once taken pride in the fact that he was able to 'hold out a gun of seven feet barrel with one hand, and had carried a barrel full of cider from a canoe to shore,' this was now brought as evidence that he had been dealing with the supernatural.

One of the tests given to the witches was the test of touch. As the 'afflicted' writhed and screamed, the accused would be made to touch them. If their screaming then ceased it was proof of guilt for the evil had been returned, if only momentarily, to the accused. This test was frequently carried out and unfailingly proved the guilt of the one involved.

On June 2, Bridget Bishop became the first of the accused to actually go to trial. Since her original hearing she had been chained up in a prison cell, seeing more and more of the accused join her. One of these was little Dorcas Goode, the five-year-old daughter of Sarah Goode. She, too, had been cried out upon by the girls and she, too, was chained, as was the custom with witches.

Although the original examinations were supposed to have been merely preliminary hearings, the evidence from them was carefully reviewed and noted by the magistrates of the Court. The only new business was the hearing of anything fresh that had been uncovered since that time. Bridget Bishop had been a tavern keeper, having two ordinaries—one at Salem Village and the other in Salem Town. The main charge against her seemed to have been that she wore a 'red paragon bodice' and had a great store of laces. The 'new' evidence against her was that she seemed to keep her youth despite her years. Various supposedly decent, upright, married men of the community testified that she sent her 'shape' to plague and torment them in their sleep at night.

The afflicted testified that Bridget had been at the sabbat meetings of the witches and had, in fact, given suck to a familiar in the form of a snake. She was taken out and searched for a supernumerary nipple, which they claimed was found between 'ye pudendum and anus.' The verdict was a foregone conclusion. On June 10, Bridget Bishop was hanged on Gallows Hill.

There was then a break of twenty-six days while the judges argued the pros and cons of accepting spectral evidence. This was the evidence of the afflicted saying that they saw the shape of the accused in a certain place when that person was known to be physically elsewhere. The consensus of opinion was that the devil could assume the shape of innocent people (this had previously been doubted) as well as the guilty.

Rebecca Nurse's case came up, and the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. Immediately there was a great uproar, and the judges expressed their dissatisfaction with the verdict. The foreman of the jury later wrote, on a certificate, 'When the verdict not guilty was given, the honored court was pleased to object against it, saying to them, that they think they let slip the words which the prisoner at the bar spoke against herself, which were spoken in reply to Goodwife Hobbs and her daughter, who had been faulty in setting their hands to the devil's book, as they had confessed formerly. The words were, `What do these persons give in evidence against me now? They used to come among us!' After the honored court had manifested their dissatisfaction of the verdict, several of the jury declared themselves desirous to go out again, and thereupon the honored court gave leave; but when we came to consider the case, I could not tell how to take her words as evidence against her, till she had a further opportunity to put her sense upon them, if she would take it. . . these words were to me a principle evidence against her.'

So after having their verdict of not guilty rejected, the jurors retired once more and came back with a verdict of guilty. Rebecca tried to explain that when she had referred to Deliverance Hobbs—who had previously confessed to being a witch, although later she joined the ranks of the afflicted—as being 'one of us' she did not mean 'one of us witches' but 'one of us prisoners.' It was to no avail. Earlier she had damned herself due to her deafness; she had not answered one of the questions put to her because she had not heard it. But her silence was taken as an acknowledgement of guilt. The Reverend Noyes excommunicated her, and Tuesday, July 19, in company with Sarah Goode, Elizabeth How, Sarah Wild, and Susanna Martin, she was hanged on Gallows Hill.

On August 19, the cart driven out to Gallows Hill carried five more: John Procter, John Willard, Martha Carrier, George Jacobs Senior, and the Reverend George Burroughs. Burroughs had been identified by the afflicted children as the 'Black Man' in charge of the coven. He was allowed to address the crowd from the scaffold. This he did in carefully chosen words that worked on the emotions of the crowd. So much so, in fact, that some started to call for his release. One of the tests of a witch was that he or she could not say the Lord's Prayer without stumbling. George Burroughs stood at the scaffold and, clearly and faultlessly, recited it to the crowd. Almost certainly they would have released him, but, as some moved forward, a young man on a horse cried out to them to stop. It was Cotton Mather. With stern words, he cautioned them against the workings of the Devil, intimating that it had been the Devil speaking to them through George Burroughs. The hanging went on as planned.

On Monday, September 19, an unusual execution was carried out. When a person was brought before the court for trial, he or she was first required to plead guilty or not guilty. No trial could proceed until the accused had so pleaded. By refusing to plead, therefore, the accused could prevent the trial altogether. To circumvent such an occurrence, the law provided a horrible punishment for anyone so obstinate. It was called peine forte et dure ('a penalty harsh and severe'). It consisted of stretching the culprit out flat on his or her back, on the ground, with arms and feet extended to the utmost in all four directions. Heavy weights of iron and stone were then piled on the body until the accused either pleaded or was crushed to death. The common name for this was 'pressing to death.'

Giles Cory was arrested for witchcraft in April. His wife, who had been in jail since March, was sentenced to death on September 10, and Giles's own trial came two or three days later. In all his eighty years, Giles had never known the meaning of the word fear, yet seeing what was done to his wife nearly broke his heart. He knew that if he did not plead, not only would his trial be balked, but the authorities would be unable to confiscate his goods and estate, as they would be entitled to do if he were proven guilty. Giles therefore refused to plead and was subsequently put to the peine forte et dure—the only time in American history that this punishment had actually been inflicted. He died without speaking.

Eventually, the accusers went too far. They started mentioning members of the Mather family; they tried to implicate Lady Phips, wife of the governor; they named the most respected Reverend Samuel Willard and, finally, Mrs. Hale, wife of John Hale himself. This proved to be too much. These accusations opened the eyes of John Hale to the point where he turned about and began to oppose the whole prosecution. He confessed that he had been wrong all along. It seemed that a number of other people had reached similar conclusions. More and more ministers came out with Hale against the prosecutions. The court recessed.

A fatal blow to the witch hunters came when a group of people in Andover, Massachusetts, on being accused of witchcraft, responded by bringing an action of defamation of character with heavy damages. This marked the end of the panic. Just at this time, the court of Oyer and Terminer was abolished due to the assembly of the general Court of Massachusetts at Boston. It was the first court elected under the new charter. The jail at Salem was filled with prisoners, and many had been taken to other jails. When the court met for the first time in January 1693, it started by throwing out indictments. The Grand Jury found bills against about fifty for witchcraft, but upon trial they were all acquitted. Some of the court were dissatisfied, but the juries changed sooner than the judges.

In May 1693, Governor Phips ordered the release from jail of all those awaiting trial, and the Salem witchcraft hysteria was over. Excommunications were erased, and claims from survivors and those who had been held from days to months, awaiting trial and almost certain death, were honored by the colony within a few years.

Five years afterward, Judge Samuel Sewell stood up in the Old South Church and publicly acknowledged his shame and repentance. For the rest of his life he kept an annual day of fasting and prayer in memory of his errors. Ann Putnam, the younger, fourteen years afterward, stood before the congregation of Salem Village church and confessed that she and others had brought upon the village the guilt of innocent bloodshed: '... though this was said and done by me against any person, I can truly and uprightly say before God and any man, I did not out of any anger, malice, or ill-will to any person, for I had no such thing against any one of them, but what I did was ignorantly, being deluded of Satan. And particularly as I was a chief instrument of accusing Goodwife Nurse and her two sisters, I desire to lie in the dust and to be humbled for it, in that I was the cause, with others, of so sad a calamity to them and their families.'

It has been suggested that what took place was, on the part of the 'afflicted children,' not fraudulent but was in fact pathological, being hysterics in the clinical sense. There have also been theories that the fits and hysterics of the children were brought on by the ingesting of native herbs, but there seems little evidence for this idea. Whatever the cause, what happened in the village of Salem, where nineteen people were hung and one man was pressed to death, was little compared to what happened throughout Europe during the persecutions of the followers of the Old Religion.

Want to thank TFD for its existence? Tell a friend about us, add a link to this page, or visit the webmaster's page for free fun content.

Link to this page: